Eddie Abd

’folded in’

10 November – 12 December, 2025

Thursday 20 November: Exhibition Launch

Left to right:

Eddie Abd, 3999, 2025, 2-channel video, no sound, 3 mins, looped. Filmed in Lebanon and on Dharug and Gundungarra Country.

Eddie Abd, holy water, 2025, fabric print stretched on canvas, 750 × 120mm, with eucalyptus water (bottled) on plinth.

Photography by Jessica Maurer.

Artist Statement

folded in is an exploration of complicity through camouflage and collage. It marks a moment of heightened awareness of our individual and collective entanglements with systems that are scaffolded by historical and present injustices.

Drawn from a speech by Indian scholar Gayatri Spivak, the expression ‘folded in’ became an entry point into self-reflection beyond the notion of guilt. The works in this exhibition are borne out of personal reckonings within myself and family and have been shaped by my ongoing conversations with colleagues, most notably Dharug artist and educator Leanne Tobin.

folded in starts a process of acknowledgment and conversation framed by personal history, the politics of the day and diasporic art making within the colony.

Credits:

Cultural guidance: Leanne Tobin

Performers: Yasmeen El Haddad, Aram El Haddad, Ludwig El Haddad, Tania Abd and Edgard Abd

Videographer: Kuba Dorabialski

Photographer: Aram El Haddad, Yasmeen El Haddad

Writer: Loubna Haikal

Live performance at opening: Ludwig El Haddad (vocals) and Fady Kassab (percussion)

This project is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

A limited number of framed digital prints by Abd are available for purchase during the exhibition, with proceeds donated to Hassala and Koorabung Project.

Please contact us for more information.

Exhibition text

folded in.

By Loubna Haikal

How do I live peacefully in the colony that participated in my displacement?

Shshsh, I’m going to tell you a well-known secret.

- I’m curious.

If you repeat it you’ll never be at peace.

- Now that I live here, nothing can disturb my peace. I’ve taken up meditation. Don’t worry. I also belong to a gym where I do yoga twice a week. I belong to a book club. I belong to a Tuesday walking group. I belong to the local library and to the art gallery. I have so much belonging here, you could say I’m now anchored in the colony. Peacefully. I’m well anchored. In concrete so to speak. I keep all my receipts, just in case. As you know I have nowhere else to go. Oh and the books I read are nothing too heavy or political. Light is our motto in my book club. You can tell me anything, rest assured you can never disturb my peace.

She came closer and whispered some words in my ear, words she feared I might feel tempted to utter. Though I seemed to be on the right track, she advised me to delete them; names of homelands I had known and lived in, other names too, of a fruit, a piece of clothing, colours, letters from elsewhere…, a long list.

‘For peace’ sake’. Her final words.

I went home and locked the front door. I pulled a dusty suitcase from under my bed and took out an old garment. With a needle and the silk threads of all the forbidden colours, I embroidered names of the forbidden homelands, the forbidden fruit, the forbidden letters, and sang the forbidden songs.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

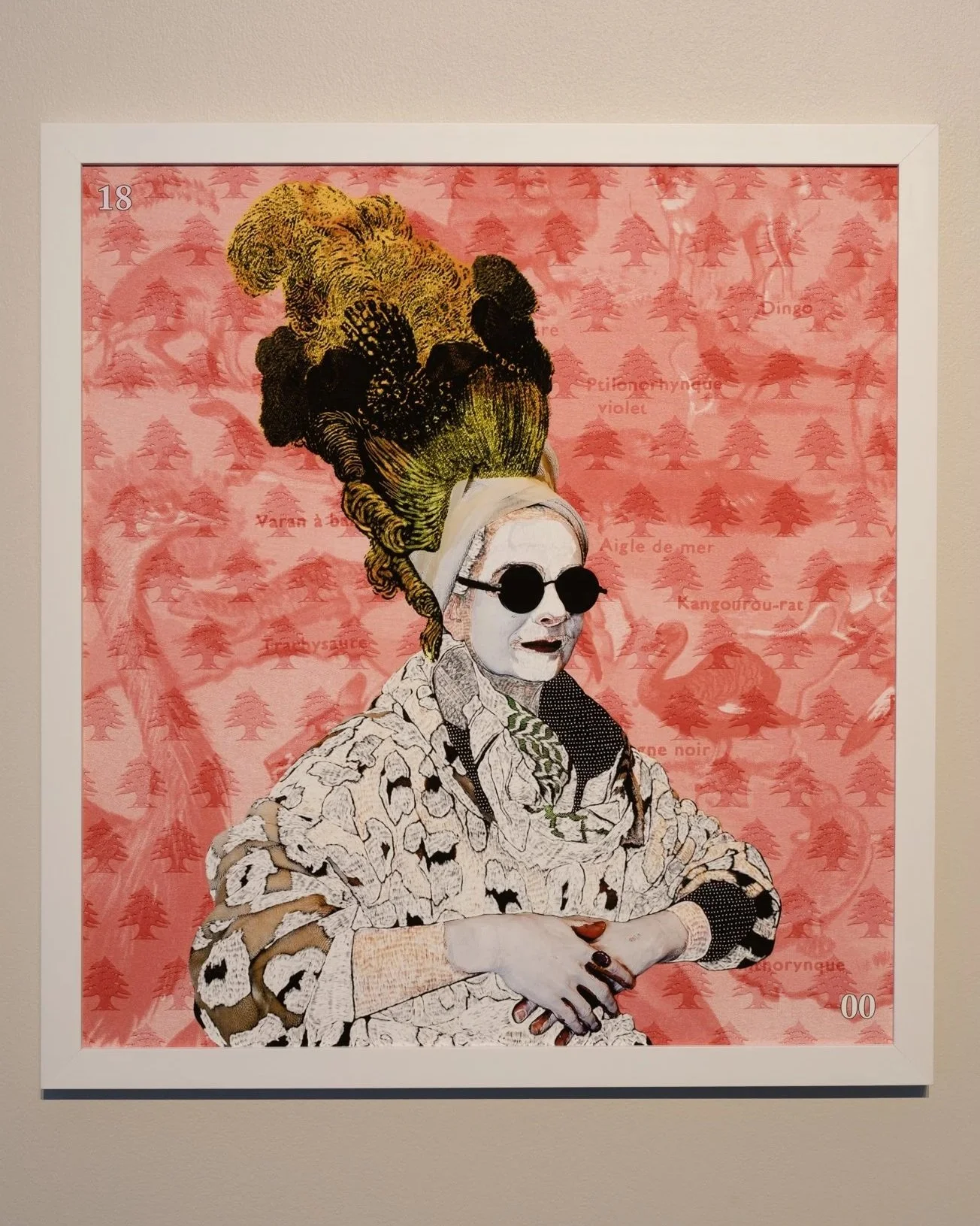

Eddie Abd, un-titled #1-3, 2025, framed digital prints (6), 250 × 250mm ea. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

Hidden folds were gradually revealed as I searched for ways to settle in the colony, and as my past, my lived experience was challenged with such words as ‘alleged’, ‘disputed’, ‘unverified’.

Not understanding the nuances of the colony’s culture, and with no prospects of ‘going back to where I came from’, I capitulated. In order to be good, I took on a benign presence, not rocking anything, but offering something positive to the system that saved me from my own country, from ‘the basket case’ it had allowed itself to become.

With time, the inherent deceitful nature of the colony became clear; the betrayal by the very system that rescued me. This knowing became the obstacle to living a peaceful life. It transformed me, an innocent participant into a complicit one, a collaborator conspiring against my homeland and the people I left behind. I was unable to fully enjoy the bounty gathered by the colony in its far and wide conquests.

Disentangling myself from the system is now a constant and daily struggle. I am exhausted. Fatigued, I spread my body on the bed, limp, no longer able to resist any terrestrial system, let alone gravity.

Eddie Abd, Awakening, 2025, fabric prints, framed (2), 600 × 110mm, ottoman with embroidered QR code, linked to video (1 min). Videography by Kuba Dorabialski. Installation photography by Jessica Maurer.

Eddie Abd, Awakening (detail), 2025. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

Eddie Abd, folded in, 2025, digital media (3). Videography by Kuba Dorabialski. Installation photography by Jessica Maurer.

When I gather myself and get out of bed, I embroider. Though embroidery is a nice activity verging on cuteness, at times it requires close surveillance by the colony as the needle may venture out and claim forbidden identities, remnants of homelands. Unbeknown to me, speech here is a privilege rather than a right. I become sneaky, and insert obfuscating patterns into the fabric, clear only to those willing to look closely, that I am still resisting; The cedar, the kangaroo, and when I feel more adventurous, the watermelon and the keffiyeh. I sew them proving to myself that I am not quite complicit. It is a way of atoning myself.

I convince myself at times, that I am just an innocent victim trying to survive. I live in the ambivalence of wanting to belong and the awareness that belonging is betrayal. When I’m out and about, I smile as a way to survive within the folds of the colony without being suffocated. Maintaining the smile in spite of the cruelty I am forced to witness leads me to feel the painful torsion of my facial musculature. I use a couple of drops of rose water and rub them around my face, I boil water with eucalyptus essence to open up my airways and deepen my breath. I unfold my arms, remove the smile off my face and reacquaint myself with my wildness.

My daily battle becomes camouflaging, as well as the urge to make a moral choice when I buy toilet paper for example, or whether to buy disposable nappies or use cloth nappies and wash them with water and soap. This creates a state of anxious inertia. Once, I was making a cake for friends coming to dinner. As I poured the wet ingredients into the dry ones, I burst out laughing, at myself. I saw myself as an ingredient unable to remove myself from the mixture even before the cake was baked.

The gloves in most of Abd’s women's hands remind us that we are complicit in most menial gestures, even in the domestic. Abd forces us not to look away. We are drawn into being complicit when we enter the space. The art, the artist and we the observers are enmeshed in the complicity of an exploitative imperfect system, as we enjoy the lighting and the temperature adjusted to preserve her art. Lending it our gaze is our participatory role in perpetuating an imperfect exploitative system. Her hands and ours are stained no matter how thick the gloves we wear.

Eddie Abd, joie de vivre (Ortagus’ hair) (1 of 3), 2025, triptych digital prints, framed (3), 600 × 650mm. Photography by Yasmeen El Haddad. Installation photography by Jessica Maurer.

We packed in our suitcases scents of orange blossoms to rescue us from exhaustion, from light headedness and episodes of near collapse. We packed waters dipped in eucalyptus leaves picked from trees born and bred in Australia, nurtured on the shores of Byblos. We wrapped with cotton cloth bottles filled with waters made sacred by St Charbel Makhlouf, the monk from Bekaa Kafra the highest village in Lebanon, whose spirit fills our being when we humans fail. These waters help heal all ruptures. When we arrived, we learnt that the commodification of occupation was one side of the equation and the receipts became proof of deceit.

It takes a while to find the language to challenge our own complicity as it is difficult to remove ourselves from the maze without abandoning parts of ourselves. Our bodies are couched in its comfortable system that has fed for decades on our displacement. One limb at a time, we unfold ourselves. Each joint defies the stiffness of conformity and re-embraces its wildness.

Morgan Ortagus, the US envoy to Lebanon, is an international brand promoting her own hairstyle. She utters. “Shaking the status quo is difficult. We are hoping for generational change. You have a choice. Either take the country back or sink further into the abyss. I am here to save those who choose and are willing to be saved at any cost. Make the choice to disarm. I’ll be back to Lebanon quite a bit. I’ll take a couple of questions. Thank you all. I got to run.”

We did not bring the plot of land that grew us and our tribe. We encased it in a red line and left it in Blat, not far from Byblos, just in case. The eucalyptus brought from Australia by the French loved our hospitable soil and propagated around it and then inside it. We sold everything outside the red line, packed it into a suitcase to secure a future. Oh, one other thing, the furniture we stretched on together with family and friends, a lifestyle we wanted to keep, that we did bring with us. We had a good life.

The eucalypts obliterated our sites of remembrance and villages where massacres had taken place. Some stones, and some edible weeds within the newly planted forests refused to disappear.

When we arrived here, the eucalyptus seemed strangely familiar and no longer in need of our tolerance. There was a mutual acceptance. They were beautiful and at home.

Eddie Abd, a trade off, 2025, triptych digital prints, framed (3), 600 × 600mm. Collaborator and model: Yasmeen El Haddad. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

Artist Bio

Eddie Abd (She/Her) is a visual artist and creative producer, working for the past 10 years on creative multimedia projects across Western Sydney.

Her approach to working with people is shaped by her own experiences and learnings as a migrant, carer, artist and broadcast journalist. She is the recipient of the 2021 Blake Emerging Artist Award and the 2022 NSW Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging). She has held solo shows at Firstdraft, Blue Mountains Cultural Centre, Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre and Peacock Gallery. Eddie studied Painting at the National Institute of Fine Arts (Lebanon) and has completed a Bachelor of Digital Media at COFA (UNSW). Eddie lives with her family on the unceded lands of the Dharug and Gundungurra peoples.